One of my biggest focuses over the past year or two has been on personal finance. It’s pretty much a staple subject of any self-improvement effort, and, as someone perhaps a bit too into spreadsheets, I’ve always been interested in my and my family’s finances.

I was beginning to dig deeper into the subject and took a lot of inspiration from the FIRE community, which stands for “Financial Independence Retire Early”. Although I have no interest in retiring in the foreseeable future, the idea of having control over both your time and your finances (i.e., the “FI” side of that) has always held an appeal.

In this two-part series, I’d like to discuss several ideas about financial independence and how my thinking here has developed over the last year. This first article will cover some of the primary tenets of the FIRE framework as well as my takeaways after experimenting with them.

Tenet 1: The 4% Rule

How much money do you need to retire? We don’t even have to use such a loaded word. How much money do you need to never have to work again? If you look at many online resources and calculators, they will base their answer off of the amount of money you earn.

This is a major pet peeve of mine, as this usually assumes you spend nearly all of the money you make. If I make 10 million dollars a year, but spend the same amount of money that I do now, I wouldn’t need more money to retire, and it wouldn’t take hardly any time to get the amount I would need. Instead, the amount of money you need to retire should be based off of how much money you spend. This can also be thought of as “how much your lifestyle costs.”

A common rule of thumb in the FIRE community is the “4% rule”. This postulates that, if you withdraw 4% or less per year of a stock/bond portfolio’s starting value (adjusted for inflation), you are very unlikely to ever run out of money. This 4% figure is called your “Safe Withdrawal Rate” (SWR). Another way to state this is, if you save up 25x the amount of your annual spending, and have it invested (hopefully in low-fee index funds), then you likely never need to earn another cent.

This is based off of something called “The Trinity Study”. Some people think the 4% rule is a bit optimistic, while others think it’s a bit conservative, but I think it is an excellent starting point. Note that this assumes you will spend approximately the same amount in retirement that you spend right now (adjusted for inflation). If you have good reasons to think otherwise, then the target would be 25x that number. However, I tend to think the best predictor of future spending is current spending.

Tenet 2: Savings Rate

If we make some simplifying assumptions, holding your spending and earnings relatively constant for a long time (adjusted for inflation), and assuming an inflation-adjusted return on stocks, then we can draw an interesting conclusion. The time until you are financially independent is dependent upon a single variable: your savings rate.

Your savings rate is simply the percentage of the money you take home that is then saved and invested, rather than spent. This is interesting because it’s independent of the total amount of money you make. If you save 50% of your after-tax income, you will become financially independent in approximately 17 years whether you earn $40,000 per year or $400,000.

Of course it’s undeniably easier to save 50% or more in the latter case, and a certain amount of money is needed to cover basic living expenses. Even so, the FIRE community is rife with stories of people achieving FI on incomes signficantly lower than the American median.

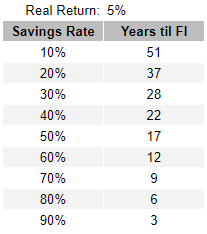

Here is a chart I calculated, assuming an inflation-adjusted average return on investment of 5% (the S&P 500’s historical average is about 6.6%). I will include a bonus section at the end on how to calculate these numbers.

This might be surprising at first, but spending plays two roles in the financial independence equation. It determines how much of your money is leftover to be saved and invested, but it also determines how much total money is needed to achieve FI (i.e. how much your lifestyle costs).

I often hear a quip that it’s better to focus on earnings than savings, as earnings are theoretically infinite, whereas you can only spend so little. I don’t buy this idea at all. For those with any waste/excess in their spending (which would include most all of us lucky enough to live a middle class lifestyle), a penny saved is far greater than a penny earned. Spending is in the denominator of the “time to FI” math, so reducing spending increases your money’s power asymptotically.

By way of illustration, let’s look at a family who earns $100,000 after taxes and spends $60,000 per year, just for some round numbers. If that family keeps spending the same amount, but earns an additional $5,000 per year after taxes (which might require earning $7,000-$8,000 before taxes), this theoretically saves them 19 months on their time to FI.

If instead that family continues to make $100,000, but reduces their spending to $55,000, then they save 32 months on their time to FI!

In order to save the same 32 months through extra income alone, it would require earning a bit more than $9,000 extra per year after taxes, which might require earning something like $13,000 before taxes. Therefore, in this case, we might be able to say something like “a penny saved is 2.6 pennies earned.”

Mr. Money Mustache is a blogger who wrote most of my favorite articles on financial independence, and he has a much better post than mine explaining these concepts here: The Shockingly Simple Math Behind Early Retirement. I see that his “years till retirement” chart matches mine, which is a nice check for my math.

My Savings Efforts

Many of the FIRE practitioners I come across online have been able to take these concepts to impressive lengths, saving 50%-75% (or a few even more) of what they earn. And many have been able to leave traditional employment in their early thirties.

I didn’t become interested in financial independence until my early thirties, and had always saved more like 20%-30% percent of my or my family’s income. This put us on a very strong foundation, but nowhere close to FI. Additionally, as stated earlier, I don’t plan to quit working anytime in the near future even if I could.

However, I was more than inspired enough to start tracking my expenses thoroughly, trying to eliminate what waste I could (and dragging my wife along for the ride :P). I also tried some random ways to save or make a bit more money that could make good material for future posts.

This improved our savings rate, but I found it far more difficult than I expected to achieve 50% or more. As a result, we’re probably still something like 10-15 years from financial independence (in our mid 40’s).

Why FI?

You might ask why I’m so enamored with the idea of financial independence if I don’t have a desire to quit working as soon as possible. This is a fair question, and I have 3 main responses.

First, I just want to do an impressive job managing our personal finances. I don’t want to sacrifice things that are important to me and my family along the way, but if being intentional with our spending can leave us with wealth down the line, I think that sounds well worth it.

Second, I’m obsessed with the idea of having options and freedom. I fully expect I would want to stay at my job and keep working if I achieved FI tomorrow, but I think I would feel very differently about it. Wanting to work and needing to work feel different at the end of the day, and you can’t help but believe you’re there because you want to be when it’s objectively true. Mr. Money Mustache has a great article on this concept: Retire in Your Mind Even If You Love Your Job.

Lastly, the future is uncertain. Things change over time - interests, abilities, job markets, etc. What if one of us suddenly needs to change our schedule, or what if we want to do something wild like pack up and move to another country? I don’t anticipate any of these, but I love the idea of being prepared for anything.

Conclusions

While buckling down to a truly impressive savings rate wasn’t in the cards right now, I still had some important takeaways from these ideas. First, in my opinion, the FIRE community has some of the clearest thinkers out there regarding personal finance. I typically will look to them for deciding where to allocate money in retirement accounts or for other similar issues. And second, being intentional with spending is the biggest lever that most of us have available to pull if we want to impact our financial futures. I plan to track spending monthly without fail.

Bonus: How to Calculate Years to FI

I calculated the numbers in that chart myself in a spreadsheet using the engineering economics formula for “future worth given an annual amount”. This formula can be found online and I got it from my NCEES FE Exam booklet I still have on my office bookshelf. My engineering friends can dig theirs up for reference!

\[\frac{F}{A} = \frac{(1+i)^n-1}{i}\]

Where:

- F = future worth = (1-savings rate)*25

- A = annual amount = savings rate

- i = interest rate

- n = time in years

I then rearranged the equation to solve for n, as shown below.

\[(1+i)^n = Fi/A+1\]

\[ln((1+i)^n) = ln(Fi/A+1)\]

\[n*ln(1+i) = ln(Fi/A+1)\]

\[n = \frac{ln(Fi/A+1)}{ln(1+i)}\]

So as an example, a 40% savings rate and a 5% real return would plug into that final equation like so:

\[\frac{ln(25(1-40\%)*5\%/40\%+1)}{ln(1+5\%)} = 21.6yrs\]

In the follow-up article, which I will post a couple of weeks from now, I will first talk about some of the downsides of an all-out approach to achieving FI. Then, we’ll go on to some other ways to frame the personal finance journey that harness incremental benefits of saving your money prior to reaching FI, as well as balancing saving for the future with living a gratifying life in the present. Thanks for reading!