The year was 2014. I was working on my Master’s degree and working at Palmer Engineering part-time. I had just taught myself the basics of Excel VBA, and it was about to pay off…

The Project

At Palmer (I also work there now!), we were working on designing two massive bridges in the Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area and had been for a couple of years at this point. One was to be over Kentucky Lake (Eggner’s Ferry Bridge), and one over Lake Barkley (Lake Barkley Bridge).

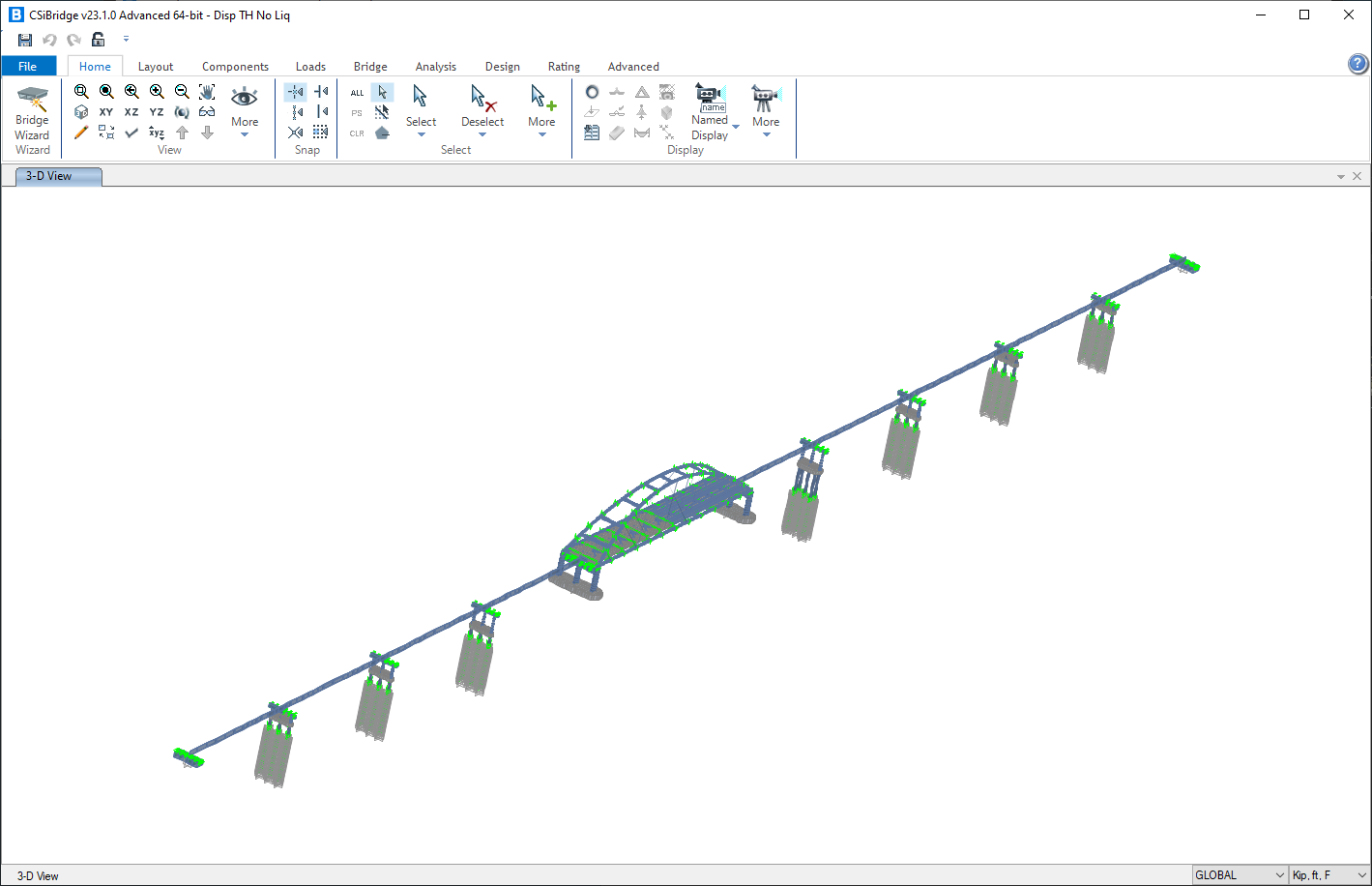

The picture above is Eggner’s Ferry bridge and how it looks now. It was an extremely cool project to be working on as a co-op and as a Master’s student. Palmer did not design the big arch span (Michael Baker designed that); we designed all of the other spans on each side of it (the approach spans). You can check these bridges out on Google Maps at the following links:

Eggner’s Ferry Bridge

Lake Barkley Bridge

The Problem

At more than 3,500 total feet of bridge length on each, this was going to be a major project no matter the conditions. However, the western part of Kentucky is close to the New Madrid fault line, so seismic performance was a major concern, and this greatly complicated the design.

One of the biggest focuses in seismic design is both the strength and the stiffness of the substructures and foundations. In this project, the foundation consisted of big 6-ft diameter pipe piles (concrete filled pipes) extending way down into the soil underwater, holding up the bridge. I’ll explain this a bit more.

During an earthquake, you can imagine the ground is moving and shaking the bridge foundation. The foundation has to be strong enough to handle this, but it also cannot be too stiff/rigid. If it’s too stiff, the ground shaking the foundation will end up shaking the superstructure (the beams and the part you drive on) so hard that it can damage the bridge.

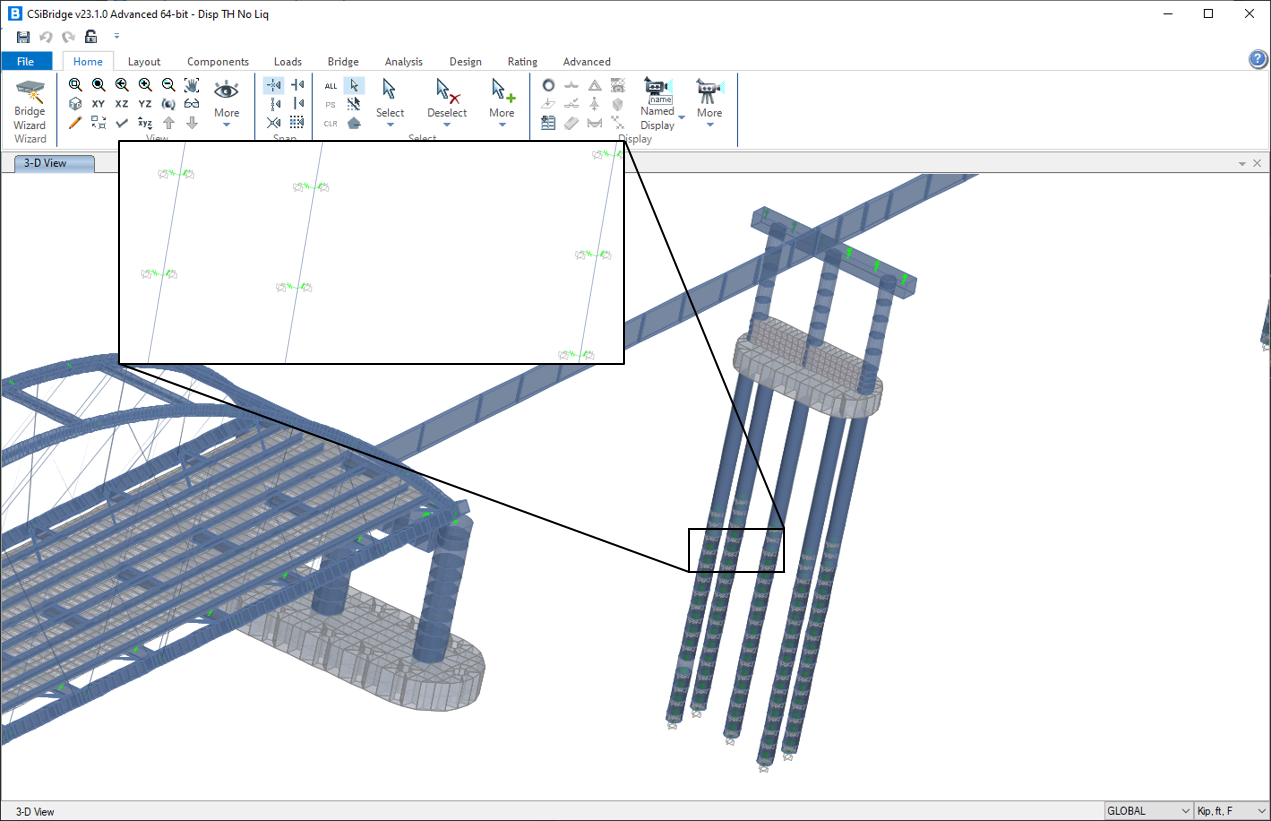

Analyzing this is very complex, as it requires estimating the loads applied to the piles by the soil, and how they move up the piles, up the pier, and into the superstructure. To do so, we used SAP2000 software, and here is a picture of one of those models.

If we zoom in on the piles under the pier, we can see some tiny springs input into the model.

These represent the resistance of the soil as the piles gets pushed one way or another. This resistance is very nonlinear, and changes with the depth of the soil and the force applied. These curves were generated in a program called “LPile” and had to be input into the SAP2000 model.

The Solution

As an intern the summer before I started my Master’s degree, I had the task of inputting the data for these thousands of springs into SAP2000, and I did it through manually copying and pasting the data from one program into the other. It took me approximately 80 working hours to get this data into the model.

Not too speedy or glamorous eh? Not to worry. I had just finished teaching myself the basics VBA in Excel, and I was beginning to learn more about SAP2000’s capabilities to interact with Excel. Notably for the approach I took, you can export or import an entire model definition to or from an Excel file. I realized I could do something with this to speed up the process, so I got to work.

I took about 30 hours to create my first major macro. It worked like this:

You have a SAP model created of the entire bridge except for the soil-springs, and you export its definition to Excel. You save your LPile output with all of the soil-spring data to a text file. You open my freshly made macro-enabled Excel sheet and the model definition Excel file at the same time. You paste the LPile output into Excel, and you click run. You then reimport the (now edited) definition file into SAP2000 and voila, the soil-springs are in there!

I was ecstatic, and this was a major win for a few reasons.

First, four total models with soil-springs had to be created, and at the time of this macro’s completion, two were finished. If each model would have taken 80 hours to enter the data, then my 30 hour time investment saved approximately 130 man hours. The macro made the process of entering the springs take approximately 5 minutes.

Second, the full soil-spring SAP2000 model was treated as something you didn’t make until near the end of the design process. You didn’t want to invest the man hours into making such a model unless you were almost positive you had the bridge members sized correctly using other checks and design methods. This macro allowed the more accurate soil-spring models to be utilized at earlier project stages, improving the feedback for the designers.

Last but not least, running this macro (and even creating it) was considerably more fun than manually copying and pasting data for 80 hours.

QAQC Considerations

In most of these case studies or examples, I plan to talk a bit about how we approach checking this work. Like I mentioned in my article Why Civil Engineers Should Learn Excel VBA Macros, I know this a major concern for engineers.

In this case, the answer is relatively straightforward. After I had finished with the model where I manually entered soil-spring data into SAP2000, someone else had the equally exciting task of checking all of my inputs. So when someone has to comb through the entire set of resulting data anyways, it doesn’t make much difference whether you input that data by hand or got a the computer to do it for you.

If anything, the macro solution was better for checking, because it’s unlikely that the code I wrote would make any one-off mistakes that can be tough to notice. Rather, a mistake from the macro is probably present on many or all of the springs and can be found more easily.

I will say that I spent a good amount of time making the macro usable for coworkers. Knowing what I know now, the user experience could have been much better, and even so, all of my coworkers were able to use it without issue. In order to help facilitate ease of use, I wrote detailed step-by-step instructions on opening and using the macro, and I added in plenty of error handling cases to the code to catch things that might go wrong.

Conclusions

This was the first of many times I have been able to use Excel VBA/macros in my work as a structural bridge engineer, and I was riding high on this success. This is what got me hooked and I kept an eye out for other ways I could use it in the future.

Looking back at the code now, almost 9 years later, there are so many ways to improve it. I did nearly everything in the least efficient way possible. I was constantly selecting and changing new cells using ActiveCell and Offset as the macro would work its way down a sheet*. I required a complicated setup where you have to export, get everything set up just right, run the macro, and then reimport; these days I would just make Excel edit the model directly. And even so, my beginner macro skills saved us over 100 hours, made everybody happier, and made me look in the process!

It was quite fun looking back at my work from so long ago. I hope it encourages you to give VBA a try! Even a tiny amount of knowledge and experience can go a very long way when the perfect use-case appears. If it’s helpful, check out my tutorial post on making Your First Macro.

*If you don’t know what that means, don’t worry! We will probably cover it in the future, but just know it’s a way to code your macros that causes a comparatively much slower runtime than other methods.)